December 13, 2017

Posted in: News Articles

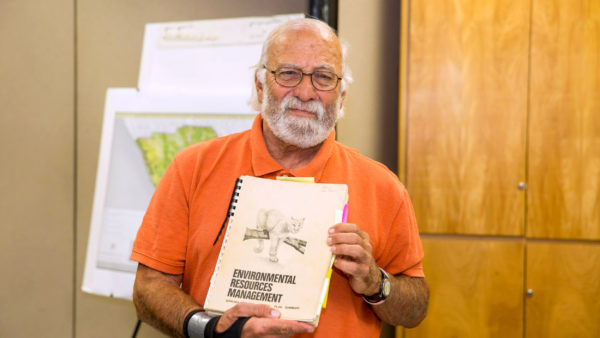

The General Plan to Vital Lands: Looking Back (and Forward) with Richard Retecki

Serendipity often intervenes at the most critical times in our lives. This was the case with Richard Retecki, a Vietnam veteran whose first “real” job began in 1972 when – out of work and on the verge of returning to his native Pennsylvania – he was hired to write detailed reports on the climate and physiography of Sonoma County. He and his colleagues developed from scratch an environmental database for the first comprehensive Sonoma County General Plan – work that would ultimately play a vital role in the creation of the District.

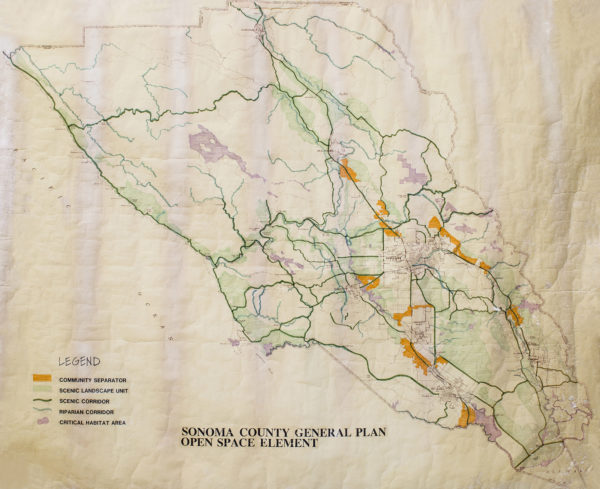

We were eager to learn about Richard’s decades-long career in environmental planning and resource management; and he obliged, answering a series of questions we provided him. An avid archivist, he has in his collection the original Sonoma County General Plan Open Space Element map. Richard provides a unique historical perspective on the preservation of Sonoma County lands along with important insights and ideas for protecting our working and natural lands into the future.

1. How did you get into planning in Sonoma County?

In August 1971, two Vietnam buddies and I moved to Jenner to start a West Coast branch of Viking Marine Biological Supply, which was owned by another Vietnam friend and located in Manasquan, NJ. We leased half of the Meredith Fisheries building in Bodega Bay. Operations were under way when the owner almost died from formaldehyde poisoning and had to close the business.

While in Bodega Bay, we were hired by Wes Mitchell, who was the primary contractor for Bodega Harbour, to do construction work—sign building, concrete finishing, and basic carpentry. Projects included a golf course clubhouse and a realty office on Highway 1. With the start of the rainy season, that job and woodcutting work I was doing in Fort Bragg ended.

I was almost ready to head home to Pittsburgh, PA when I stopped to visit another Army buddy in Petaluma. In need of work and money, I went to the VA office where I noticed a 3×5 card announcing that the County was recruiting soils engineers, hydrologists, geographers, and others to research and compile from scratch an environmental database for the first county comprehensive General Plan. I left the VA office with the card in my pocket and the recommendation to read Design with Nature, an influential book by Ian McHarg about environmental planning using an integrated ecological approach.

I called the County on a Wednesday, was interviewed on Friday, and—along with five others—began work the following Monday, March 6, 1972. My salary was $3.27 per hour through the federal Emergency Employment Act program. I was hired to write comprehensive reports on the climate and physiography of the county. Funding was only guaranteed for three months through the EEA. We ended up working almost two years, in three-month increments, until the County hired us as permanent employees.

For those of us on the Advanced Planning team, this was our first “real” job. We were a young, creative group—most of us were in our early to mid-20s—who worked hard to produce a document that was exemplary, and that still holds true today.

2. What aspect of the plan are you most proud of having contributed to?

The Environmental Resource Management Element (ERME), which was a goals, policies, and recommendations document that merged four required elements of the General Plan into one document. The ERME would complement the environmental database and provide guidance and facilitate a flexible system with which to implement the General Plan. It was a working tool to develop a responsive environmental planning program. The document provided goals, policies, and recommendations for 14 categories of environmental planning—resources, hazardous areas, historic preservation—which also included Regional Parks. Landscape Units and Handbooks were established and mapped as areas within which environmental data could be conveniently assembled and analyzed. Each Landscape Unit was a localized environmental planning area that served as the focus for policy evaluation, impact assessment, and growth analysis.

The seven land-use alternatives were based on projected populations of 380,000; 430,000; 480,000; 510,000; 540,000; 590,000; and 630,000. The environmental data base was used to evaluate the impacts of each GP alternative. Seven land-use alternatives with different levels of population, employment, transportation, housing, and environmental protection were planned for, displayed, and evaluated by each city, special district, planning commissions, and the various members of the Boards of Supervisors. The low population level was 380,000, or Slogrowth, and the highest population level was 630,000, or Gronorth. There were projections of a population of 480,000 in Sonoma County by the end of the century. The Board of Supervisors chose the 430,000 land-use alternative, with the County actually having around 415,000 in year 2000. The county’s population now is nearly 520,000. The city-centered approach with community separation and environmental protection is still holding and intact.

After the 1976 Supervisorial recall, I was one of three remaining Advanced Planning staff (24 were let go) to take the Plan through two years of intense review and revision to final adoption in March 1978. This was truly a workout. The beginnings of the Coastal Plan and writing the first work program for the Sonoma County LCP (Local Coastal Plan) was a creative and enjoyable undertaking. Finally, I was responsible for developing the programmatic and comprehensive EIR for the final ERME documents—also a workout!

3. What are some key concepts that you helped develop in the 1978 General Plan that have been accomplished/implemented by the District and other county agencies?

Environmental integrity and sustainability in relationship to development; the ERME; a mechanism to purchase and protect unique natural resource lands and agricultural operations (the District); a thriving Regional Parks Department; and the Local Coastal Plan. City-centered concept; community separators; rural and urban mix of land uses; and inter-agency cooperation and funding to increase access to the Russian River and the coast.

4. How has the landscape of Sonoma County changed over your years as a planner?

Cities are larger but still separated; community separators are being maintained; loss of the diversity of agriculture to vineyards; the inefficient growth of rural residential development throughout the County; areas of the coast are built out; enormous effort by public agencies and nonprofits to designate and protect valuable natural and agricultural landscapes and operations. Development and implementation of a strong Local Coastal Plan. Slow but steady completion of the Sonoma County segments of the Coastal Trail.

In the early 70s, only 1.8% of the county was protected or available for public use. Today, that percentage of protected land is close to 20% thanks to the District, public agencies and nonprofit organizations. Major highways are larger and the SMART train is running.

5. What would you like to see Sonoma County look like in the next 40 years?

That the natural landscape and environment will still be recognized as valuable and unique and continue to be protected for the future. Cities will be separated and community separators will be intact. The coast will be more protected than it is now and the California Coastal Trail will be continuous from Mendocino to Marin. There will be an interconnected park and trail system throughout the county. That the physical integrity of each landscape unit will be maintained and protected to ensure the preservation of our physical and landscape diversity. That the County will, using environmental criteria, limit and direct rural residential development into appropriate serviceable areas. The County will have adjusted and adopted the planning strategies necessary to confront the impacts of sea level rise to our coast, parks and bay and coastal lands.

We will be a totally green-powered county using as many types of green energy as possible.

The fire damaged areas of 2017 will be rebuilt in a sensible manner and protected from future fire storms. Smart and firm land-use policies will regulate rural residential development into areas that are serviceable and not in high fire-hazard or flood-hazard areas. Earthquake and seismic-hazard areas are another matter in and of themselves.

Looking back, my success in long-range planning and other efforts has been dependent on the people I worked with. If you can design anything about your work, it should be the people you work with. That has made all the difference for me—having smart, fun, hard-working peers. We took on a tough and complicated job and did it very well.